Several years ago my wife, son, and I went to Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota. It was a beautiful and majestic experience.

Several years ago my wife, son, and I went to Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota. It was a beautiful and majestic experience.

We marveled at the natural splendor of the Black Hills region and the manipulation of the natural world by sculptor Gutzon Borglum. And we didn’t want to miss Crazy Horse Memorial either. A day was spent roaming the Lakota Chief’s surroundings, imagining what the mountainside will look like when finished.

Both memorials were time well spent.

Seeing the four former presidents faces sculpted into the mountainside at Rushmore (and the Oglaga Lakota leader) made me ask myself a question: if I were to choose four faces from colonial America to be carved into stone who would they be? My only criteria I gave myself is the individuals had to be born before 1776.

I know not all the Presidents sculpted at Rushmore were from colonial America, aka…Lincoln and Roosevelt. But in my mind the four faces for a new Rushmore need to be members of the newly found American experience, contributing something unique to American history.

After some thought, I came up with four figures that should have their own Colonial sculptural presence. I chose them not only for their unique life, but because they are out of the mainstream of American thought, representatives of counter-cultural influences and causes within the American experience. I place them in chronological order.

Pocahontas (c. 1596-1617). Take with a pinch of salt the Hollywood renderings of this wonderful woman and recognize that she was a bridge between two distinct cultural worlds: Native American and European (and all the variations within each). Daughter of a chief from Algonquian-speaking tribe, she was one of the first Native American women to marry a European, John Rolfe. Her marriage to Rolfe instituted 8 years of peace known as the “Peace of Pocahontas.” Some speculate she was a spy. Prior to her rise on the international stage, Pocahontas was imprisoned, taken to foreign lands, and largely misunderstood—by both Natives and Europeans (she converted to Christianity, which made some upset). Yet, Pocahontas stood tall in the face of it all and influenced generations of people, both native and non-Native.

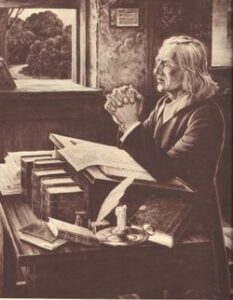

Christopher Dock (c. 1698- 1771). What makes American education unique, standing out from European education? The answer is too complex for a short article, but we find traces of it in the work of German émigré, Christopher Dock. Immigrating to Pennsylvania, Dock became a teacher, farmer, hymnist, and artist (Fraktur). Renouncing harsher forms of education (he was, after all, serving the Mennonite community), Dock introduced uniquely American education by valuing character building, discussion, listening, and positive reinforcement to train students. Dock valued the content of character, helping shape the virtues of the students he taught. Dock died in his classroom at his prayer desk, where he prayed daily for each student.

Christopher Sauer II (1721—1784). One of Dock’s students and son of the first major German-speaking newspaperman and printer (he ran the rival newspaper of Benjamin Franklin), Christopher Sauer I, Sauer II inherited his father’s love of printing, political insight, character, and quest for freedom . As one of the first people persecuted for his beliefs in Colonial America (the new Americans deemed him a traitor for not supporting the Revolutionary War and giving too much leniency to the “Indian Problems”), Sauer II was stripped of his business and home. A member of the Brethren Church in Pennsylvania, Sauer was a Christian pacifist and paid dearly for it. As a representative of freedom of religion, political consciousness, and freedom of worship and thought, Sauer II—much like his father and Brethren leaders—was a voice of conscious for the newly established American experience.

Cyrus Bustill (1732-1806)—Quaker businessman, brewer, and abolitionist, Cyrus Bustill was born in New Jersey to lawyer Samuel Bustill and Parthenia, a former slave, making Bustill a slave by birth. Some speculate that Bustill was one of the enslaved individuals freed by Quakers between 1763 and 1796. Bustill joined the Revolutionary War cause, not as soldier, but as baker (some reason to protect his Quaker pacifist beliefs). He was recognized by George Washington for his efforts. After the war, Bustill rose to prominence in Philadelphia, becoming a leader in business (baker and brewer), education (first African American school teacher in the city), and charity work. As a founding member of Philadelphia’s Free African Society he helped the poor and destitute, establishing a school for children. As a landowning man of color, he bought land and started various business endeavors. His family heritage includes artists (David Bustill Bowser, Paul Robeson, Robert Douglass, Jr.) and educators (Sarah Mapps Douglass and Gertrud Bustill Mossell). If family lineage tells something about the person, Bustill’s legacy looms large.

You may disagree with my list; that’s ok. One of the great aspects of America life is the willingness to disagree and still live alongside one another in relative peace. Maybe my list causes you to think who you’d place on your Mount Rushmore. Go ahead, make a list. It’s a great exercise.

For my part, choosing a diplomat (Pocahontas), a teacher, farmer, and artist (Dock), a printer-journalist (Sauer), and a businessman-activist (Bustill) gives support to the argument that America was built on hard-working individuals, common men and women who lived uncommon lives for the good of neighbor and country. All weren’t perfect, but believed in a Perfect God who creates beauty from the banal. And unlike the four Presidential politicians on Mount Rushmore, these four women and men are wonderful reminders that America wasn’t founded on politics alone, but by individual persons engaged in faithful and fruitful living.

For those wanting more information about the above-mentioned people, I recommend the following biographies:

- Pocahontas: Medicine Woman, Spy, Entrepreneur, Diplomat, Paula Gunn Allen.

- Christopher Dock: Colonial Schoolmaster, Gerald C. Studer.

- The Christopher Sauers, Stephen L. Longnecker, Brethren Press.

- Cyrus Bustill. Sadly, there are no major biographies about Bustill (yet), but you can read about his life and influence in Philadelphia Quakers and the Antislavery Movement by Brian Temple, and Lift Every Voice: African American Oratory, 1787-1900 by James Foner and Robert James Branham.