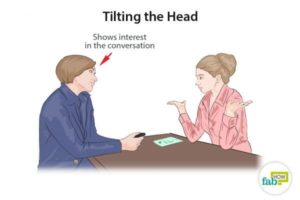

The head tilt as a means of developing curiosity and a metaphor for finding Christian in culture.

ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO—Wait. Wait. Not yet. I’ll tell you in a minute.

ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO—Wait. Wait. Not yet. I’ll tell you in a minute.

For now, I’m watching a lady, the one by the abstract painting on the wall of the museum. She’s wearing sophisticated blue pants and has small, round glasses on top of her head, pulled up from her inquisitive eyes.

She’s staring at the painting on the wall, a Franz Kline I think. She keeps walking horizontally in front of the painting, then vertically towards the black and white abstraction. She puts her left hand to her hip, taps her behind. She looks at the brochure in her right hand, then back at the painting. She follows this routine for a few minutes, mumbling to herself.

And then she does it. I knew it was coming.

She tilts her head. I pegged her: she’s a head tilter.

I’ve seen it many times before: a man or woman standing in front of a painting at a museum— or maybe looking at computer screen or digesting an idea someone just said, contemplating, wondering, nodding. Then it happens— he or she tilts his or her head.

Curiosity arises.

The tilt of the head is a signal— a sign that indicates interest, giving awareness. It is a position of inquisitiveness or an indication of uncertainty. Tilting a head conveys that the person is observing and interpreting. In some societies, a head tilt is a form of submission and humility. By exposing the neck, the person is giving someone his or her life. Even animals—dogs most notably— tilt heads.

It’s a universal sign.

It’s a universal sign.

To a large extent all people are head-tilters. After pondering, pressing for insight, and discussing a host of things —we all, at some point in our life, tilt our head, seeking a new perspective, a fresh vision of what we think, see, or believe, asking “What’s all this about?”

If we don’t tilt our head physically, we sure do it metaphorically: we ask, seek, search, and contemplate. The head tilt is part of the human condition. The head tilt is connected to a heart-tilt, bridging our mind to our emotions, a means by which we conjoin our brain to our body, showcasing the common characteristic of interest and inquiry about this thing called life.

The definition for “tilt” is simple. The noun means a “slopping position or movement,” like, the tilt of the earth. The verb form is “to cause to move into a sloping position.” As one can surmise, both definitions require movement, from one position to another. In the verb case, someone who tilts his or her head moves it from an upright position to an offset position.

It’s this offset position that is fascinating to me.

The body language conveyed by an offset head indicates curiosity, interest, observation, understanding, and, as pointed out above, humility. And figuratively, an offset head shows a movement in consideration, empathy, an agreement or disagreement. In short, the person who tilts his or her head is trying to understand the object before them, a deepened curiosity.

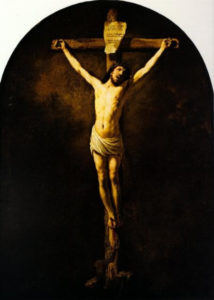

Head tilt. It’s real. And if you believe Rembrandt van Rijn—the famous Dutch painter—Jesus may have tilted His head while teaching or praying. In several beautiful paintings, van Rijn shows Jesus tilting his head, eyes fixed, a gaze of love and forbearance. Interesting. Why was Jesus tilting his head in Rembrandt’s paintings? Was he showing compassion? Contemplation? We can only guess.

But what we do know is that Christ tilted His head on the cross. As John 19:30 conveys, Christ bowed His head—a type of tilting, submitting, humbling—and gave over His spirit. What Jesus came to do was almost accomplished. With His death, He fulfilled His Father’s will. But with His resurrection, He accomplished what He came to do: bring new life, a new vision for the world—the Good News! This “theology of the cross” as Martin Luther likes to say, brought power from the pain; hope for the hurting; life for the lost. A new world was birthed.

And we in the various civilizations around the globe are recipients of that world. We call it the Judeo-Christian worldview. It helped craft our character, define our domains, and provide us with a purpose and plan.

In short, a Christian culture was born.

And though this Christian culture has wavered the past few decades, we can’t escape the fact that we inherited something grand: cathedrals and hospitals, literature and music, paintings and poems, all dot our landscape like flowers in a field.

The question I ask: can we see Christ in the midst of this fading Christian culture? I submit, we can. We just need the eyes to experience and the heart to hear that Christ is alive and well in the most unexpected places—our culture. Like basic inductive Bible study tools, we need to observe our culture, interpret it through the lens of Christ, and apply it to our lives—when necessary.

So next time you see a person tilt his or her head in front of a painting—like the woman described at the beginning of this article, thank God—and tilt your head with them.

In Pt. 2 I’ll give some thoughts on how to use the acronym TILT on finding Christ in Culture.