ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO (ANS)—I marvel at a person that is able to go from prison to prominence. But this is the case with poet, Jimmy Santiago Baca.

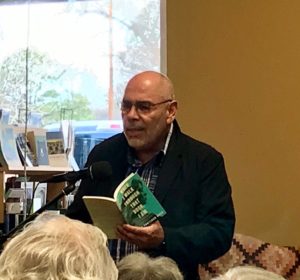

Jimmy Santiago Baca

Born in 1952 in Santa Fe, New Mexico and deserted by his parents by age ten, Baca lived with his grandparents and in an orphanage before finding his way to prison in the early 1970’s for a drug offense, leading to a gunfight with the FBI. While in prison Baca taught himself to read and write, falling in love with poetry, eventually sending his work to famed English-American poet Denise Levertov, a Christian poet.[1] Upon his release in 1979, Baca began a journey of writing and renewal. His passage continues to this day, with dozens of books, a family that he loves, a speaking schedule that takes him around the world, movie deals, and other such imaginative ventures; Baca’s creativity seldom runs dry.

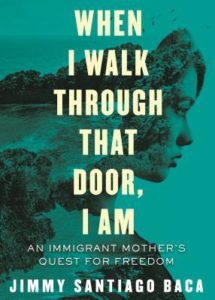

When I Walk Through That Door, I Am

With his newest release, When I Walk Through That Door, I Am, Baca continues his creative course with a narrative poem about an El Salvadorian immigrant woman, Sophia, coming to America. Along the way, Sophia is raped, misused, and belittled. But her strength—and ultimate arrival in the United States, brings hope and renewal in unexpected ways.

As I sat in a packed bookstore of people—along the Rio Grande River in Albuquerque, Baca read the first portion of the poem, roughly 32 pages. The poem reads like a story, so the narrative moves quickly. With subtle beauty and brutality, Baca makes both political and personal statements of love, longing, and the limits of borders within the poem.

After the reading, Baca opened up for a time of questions. He was honest with his answer when asked if he choose the name Sophia (meaning “wisdom”) purposely. His answer: “No, it just came to me.” He shared a story about being confronted by a feminist during a recent reading in New York (‘what gives a male the right to write in a woman’s voice’), Baca replied with respect, but retort: “I write what I feel.” And when asked about men and women who gravitate towards gangs (something Baca did as a youth), he said they “need guidance and essential opportunities.”

We’re In This Together

Baca waxed philosophical in much of his post-reading discourse, stating, people tend to “spend a lot of time trying to kill what is good in you. A lot of us do. In fact, we get on the freeway each morning to drive to a job we hate…rationalizing our life away. And I decided I’m not doing that. I’m going to spend my time with people—brothers and sisters…with everybody…. Whoever invented that thing [the walls between people]—I’m white, I’m Chicano… can shut up. We’re in this together.”

Baca was honest with his personal history (a drunk, an addict, womanizer, and criminal), until he “came back to his senses.” What his senses are, I do not know. He mentioned that he meditates, and jokingly referenced his need to go to church each day. But in the end, Baca recognizes the frailly—and strength— of the human condition, which is prominent When I Walk Through That Door, I Am.

I Need Hope

So more than just a poem with political implications—which are definitely there, When I Walk Through That Door, I Am is poem about humanity—the good, the bad, and the ugly. As one Goodreads commentator stated, “It reads like an epic Greek tragedy.” Others comment about the “over-the-top” scenes (meaning, unrealistic), but summarizes it as a “pure, lyrical” work.

And if Baca is correct by stating that he recently received news that the book may appear on a New York bestseller list, it’s a marvelous feat for a poem; seldom do poems find a position on a national bestseller list.

In the end, Baca calls When I Walk Through That Door, I Am “a gift from New Mexico to the world,” concluding, “I can live in this world, but I need hope.”

__________________________________

[1] Denise Levertov was born in 1923 in Ilford, England. Her father, Paul, was a converted Hasidic Jew and later an Anglican Priest, having emigrated from Germany via Russia. Her mother, Beatrice, was of Welsh origins. In her early life, Levertov knew she wanted to be a poet, sending her work to the famed American-English poet, T.S Eliot. She moved to the US with her soon to be husband, Mitchell Goodman; they were later divorced. Levertov’s early work was laden with political overtones, but upon her Christian conversion in 1984 her work took a spiritual direction, encompassing themes of faith, doubt, and affirmation. She died in December of 1997.